Bookmarking this for future reference. The video is by Maurizio of The Perfect Loaf.

I now realize there wasn’t necessarily a single cause behind the somewhat flatter loaf which came out of the oven the other day. I assumed it was over-fermentation or over-proofing. The higher hydration (wetter dough) was likely a factor too. Or perhaps the sole factor.

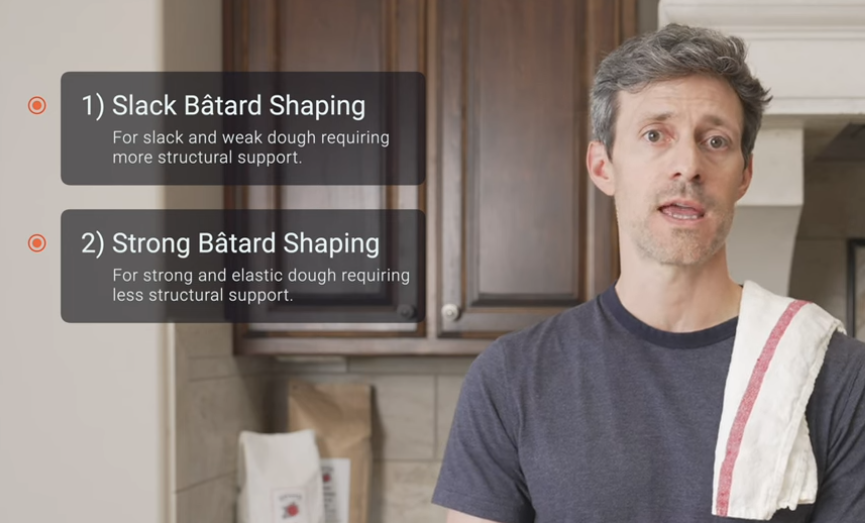

The video contains two demonstrations.

The slacker dough can be caused by overfermentation, minimal or hand mixing, higher hydration, lower protein content in the flour, or some combination. It will require more extensive shaping (more motions) to get the dough “into shape, so that it holds its shape, from shape time all the way up to bake time.”

I’m now more interested in the shaping part of the process. In fact, my overall sourdough interest and skill level – or at least my interest in improving my skill – has recently expanded beyond the “everything in the pyrex bowl” approach I’ve been coasting with for the past four years, since I got started with sourdough. Following Maurizio’s suggestion to keep a notebook has been more helpful and inspiring than I would have predicted.